What if it gets worse?

Okay, but what if it doesn’t?

Fear can be a significant barrier to improvement and contributor to increased pain, sensitivity and avoidance behaviours.

Injuries occur, and our bodies heal. But the regression of pain is rarely linear.

Is there a belief that a movement is harmful, a subconscious expectation of pain, a memory that is associated with a heightened emotional experience, a belief that we are more vulnerable to injury or structurally fragile?

What about the feeling of disempowerment when a person is told to avoid movement just in case?

If a patient presents to you with pain and negative beliefs about movements associated with pain. Try this…

Patient: “I have been told that I can’t run/exercise because it might make my pain worse…”

Clinician: “Ok, what if it doesn’t? What if you do less for now, or start slowly and build up? Let’s find out how much you can tolerate now, and we can start with that…”

Patient: “What if it starts to hurt?”

Clinician: “If it starts to hurt, we can adjust. Pain can gives us an idea of your current capacity/level of sensitivity, we can then modify the movement type, total volume or the intensity. Let’s see what you can manage for now.”

Patient: “Is it possible the pain will get worse?”

Clinician: “Yes it’s possible, in the same way that anything is possible. Pain and flare ups are a completely normal response, this does not mean it is doing more damage or that you are back to ‘step one’. It is also possible that you will make it better and make a full recovery, let’s focus on helping you move with more comfort.”

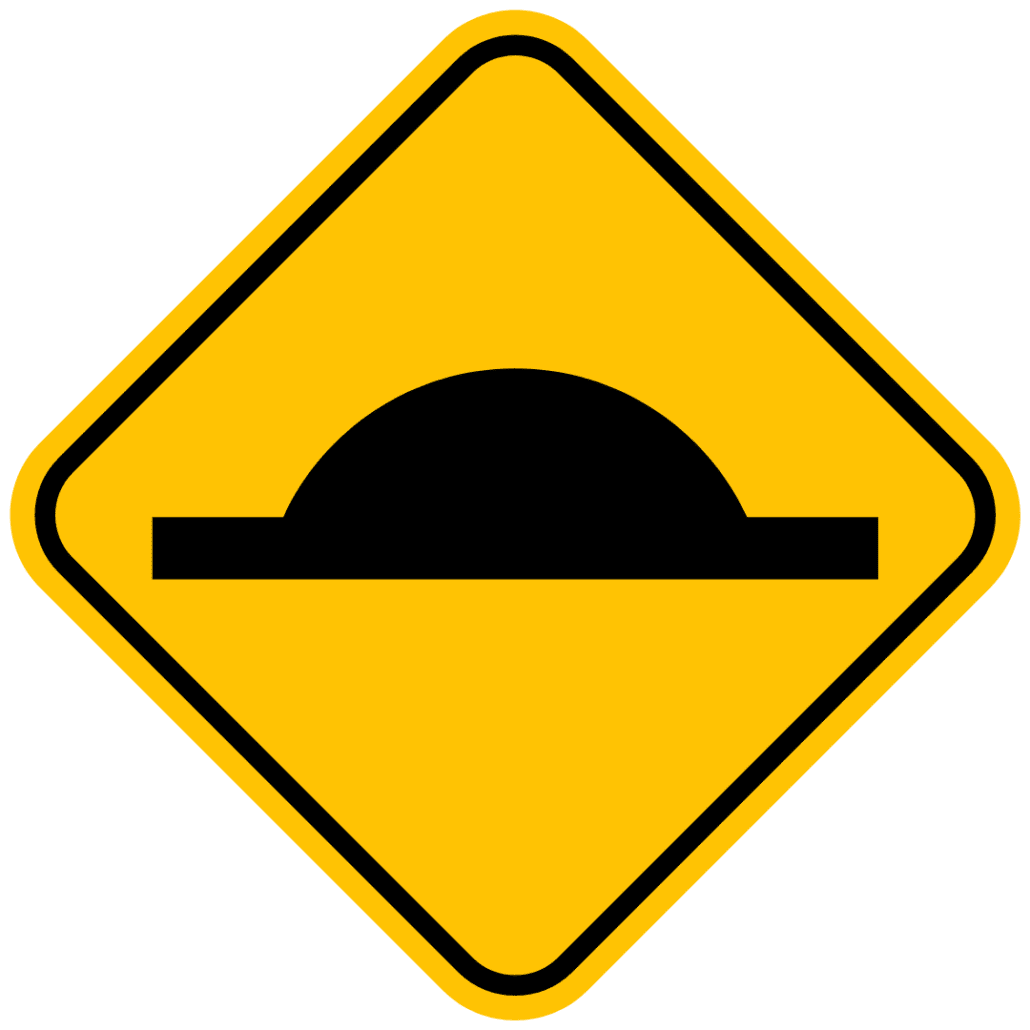

It is important to remember that flare ups are completely normal, this doesn’t mean that we should avoid everything “just in case” it just means that when it is sensitive we modify activity levels and work our way back towards your goals. Just like any road, there will be speedbumps, proceed slowly, and return to the speed limit.

Try some mindfulness:

When a patient has a painful movement, for example in low back pain, it may be painful to bend forward:

➡️ Ask your patient to work towards the painful movement to a point where it is an acceptable level of discomfort.

➡️ Ask them to tell you about what they are feeling. Your patient may describe a physical sensation such as sharp, pulling, stabbing, pressure etc. but try to explore beyond that.

➡️ Ask your patient: “What do you think is stopping you from going further?”

(It is not uncommon to receive a superficial answer such as “the pain”), but finding out what is the underlying emotional experience is important.

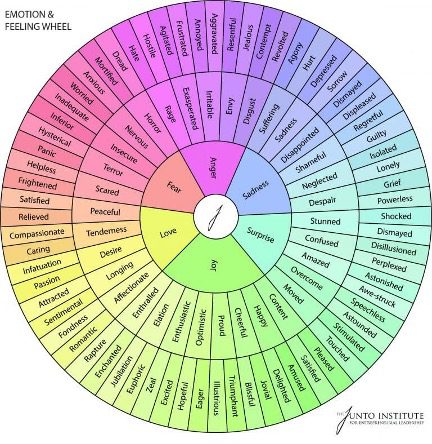

➡️ Ask your patient: “If you could label this feeling as an emotion(s), what would that emotion be?” These emotions may include, anticipation of pain, worry, fear, apprehension, a lack of trust in their body, feeling powerless, angry, irritable, sad, disappointed, a loss of control, etc.

Figure 1. The emotion and feeling wheel is a visual tool that helps to identify, understand, and articulate emotions by categorising them into core, secondary, and tertiary levels for better emotional awareness and communication. Start with a core emotion in the middle and then select a secondary emotion in the middle circle that is most relevant to the experience and then label a tertiary emotion in the outer circle.

Perhaps, the emotion that is tied to the sensation is what is contributing to the behavioural change and protective responses.

Diving deeper… Ask: “What do you think is the reason for this type of emotional response?”

It may be tied to thoughts and beliefs of worst case scenarios, dangerous movements, how they initially hurt their back, what they have been told or what they have read, how it might impact their life if it gets worse, how it might impact their relationship or family life, the implications on their work, sport or hobbies.

Take some time to recognise the feeling, label the feeling and not just the sensation then focus on spending some time to get more comfortable with the feeling.

Use mindfulness to come back to the present moment and not letting thoughts and emotions run wild when there is an uncomfortable sensation by trying to make sense of ‘what it means’. Simply recognise sensations, recognise emotions and feelings and let them go as opposed to catastrophising what ‘could happen’ or what ‘might happen’.

Recognising the emotion that is attached to the movement can help to shift the attention away from a physical and biomechanical view by exploring different movements and position, labelling emotions can help a patient to understand some underlying contributors to their pain experience.

Our role should not be telling people to avoid something ‘just in case’… our role should be to help to reduce fear of movement and return to activities that they enjoy as soon as possible.

Consider a multifactorial view of pain as a sensory and emotional experience. Focus on the future and not the pain. Focus on what they can do and not what they can’t. Focus on the person and not the structure.