Referred Pain

What is it?

Referred pain can be confusing and often misunderstood. Patients regularly present to us in clinical practice with referred pain symptoms. But what is it? Where does it come from? and why can it be so different?

Firstly let’s start out by stating that referred pain is different to neuropathic pain. Referred pain is felt away from the site of the painful stimulus and neuropathic pain is felt along the distribution of the nerve.

Referred pain is often experienced as dull, aching and gnawing, and is sometimes described as an expanding pressure (Bogduk 2009) This pain is often poorly localised. Neuropathic pain is often described as lancinating, shooting, crawling and electric etc and it has a specific location of symptoms.

Where does it come from?

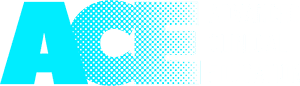

During embryogenesis the formation of the somite consists of the dermatome, myotome and sclerotome.

The Dermatome provides innervation to the skin, the myotome provides innervation to the muscle and the sclerotome provides innervation to the bone, and tendons.

This innervation occurs at each spinal segment. Therefore each spinal segment will have a specific area of skin, muscle bone and associated tissues that is supplied by a single nerve root.

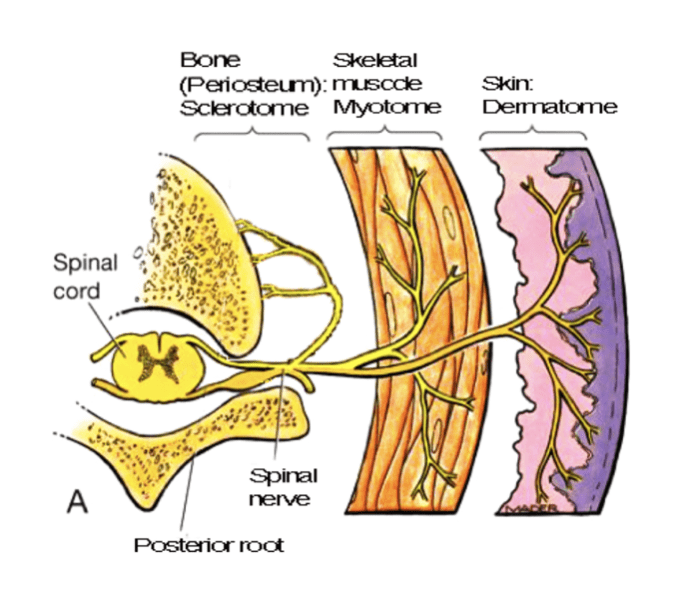

All afferent sensory information from different tissues arrives at the dorsal horn of a single spinal segment.

Why does referred pain happen?

We don’t really have a clear reason for referred pain. However, the most accepted theory is the convergence theory.

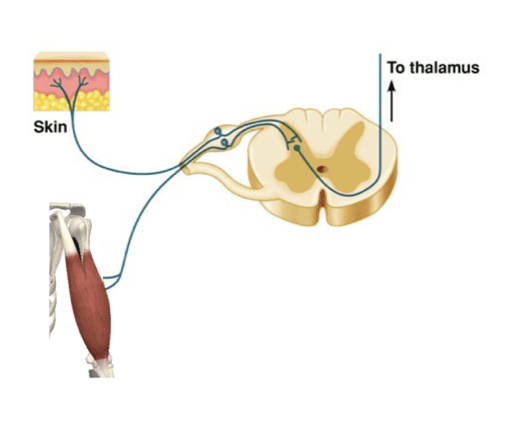

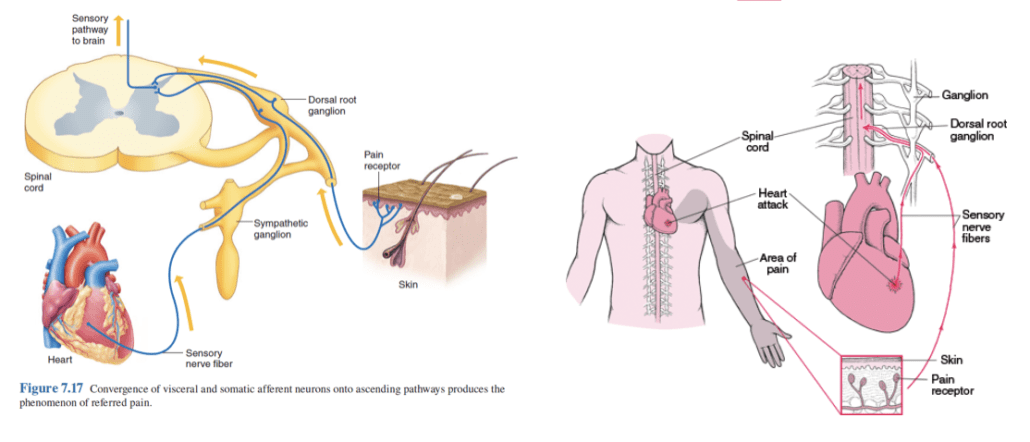

Sensory information arrives from the periphery via a 1st order neuron where it synapses with a second order neuron at the dorsal horn, this second order neuron then send the message to the thalamus where it is sorted and then delivers the message to the somatosensory cortex via a third order neuron. The somatosensory cortex is responsible for receiving and processing sensory information.

Because so much sensory information from the periphery is sent to the dorsal horn of a particular spinal segment these messages converge onto the same second order neuron, and therefore when this message reaches the brain it can be confused about the exact location of the painful stimulus. This is known as a ‘projection error’.

Consider the classic example of a heart attack. The pain is felt into the shoulder, arm and jaw. When this noxious message makes its way to the brain, there is confusion in the cortex as to the exact structure / location of the painful stimulus. The pain is then misinterpreted and experienced in the somatic tissues around the shoulder and into the arm.

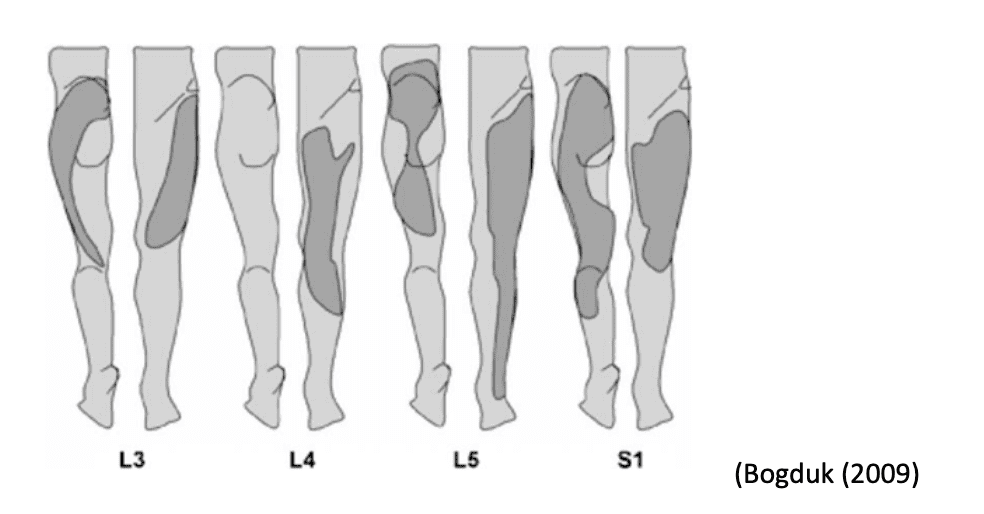

Another example may be from an L5 disc injury. The noxious input may be coming from the disc, joint, muscles, or nerve. The nociceptor threshold is lowered due to mechanical and/or chemical irritation. All tissue that receives input from the spinal segment of L5 will synapse with a second order neuron at the dorsal horn of L5. This message will be sent to the thalamus where the message can be confused about the exact location of the pain and therefore the areas that have a larger somatic representation in the cortex will be where the pain is experienced.

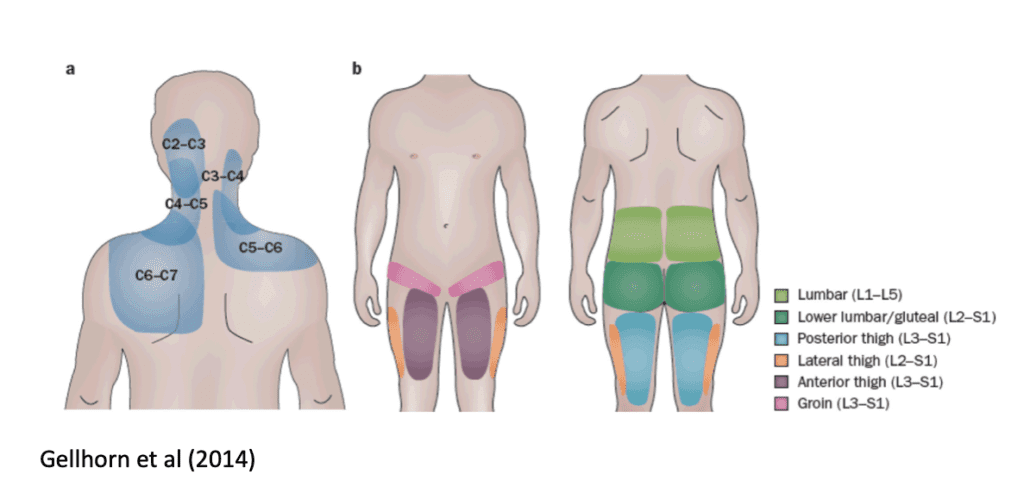

Somatic referred pain may look like this:

Although the noxious input is coming from a single spinal segment, there is greater neural representation in the somatosensory cortex from other somatic structures that converge on the same spinal segment so the pain is experienced in more distal regions.

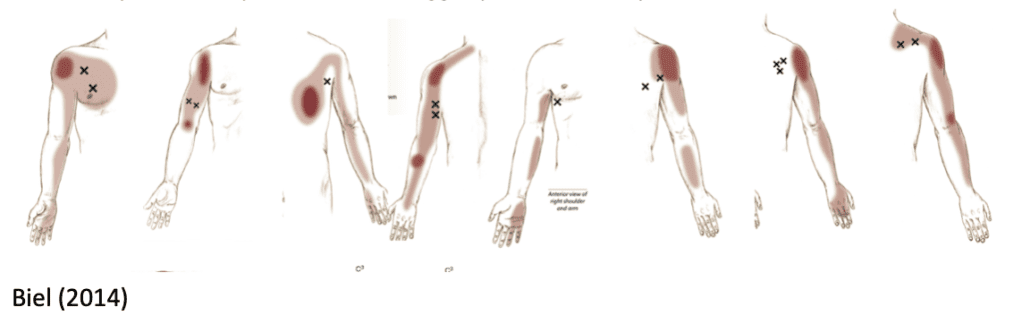

I am sure you are very familiar with trigger point referred pain…

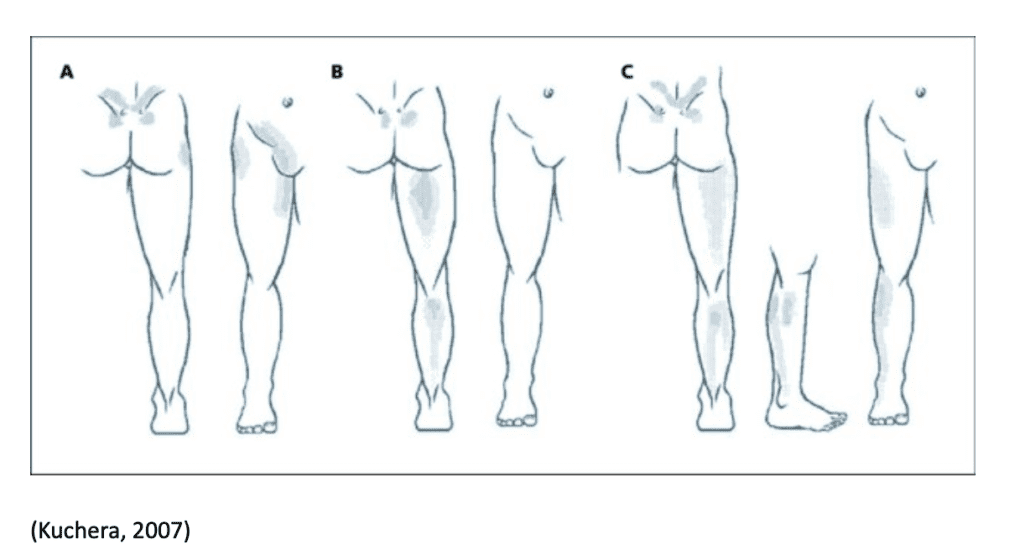

But it is interesting to note that referred pain patterns can arise from other areas also such joint related pain, which may be represented as a sclerotomal pattern which may look like this…

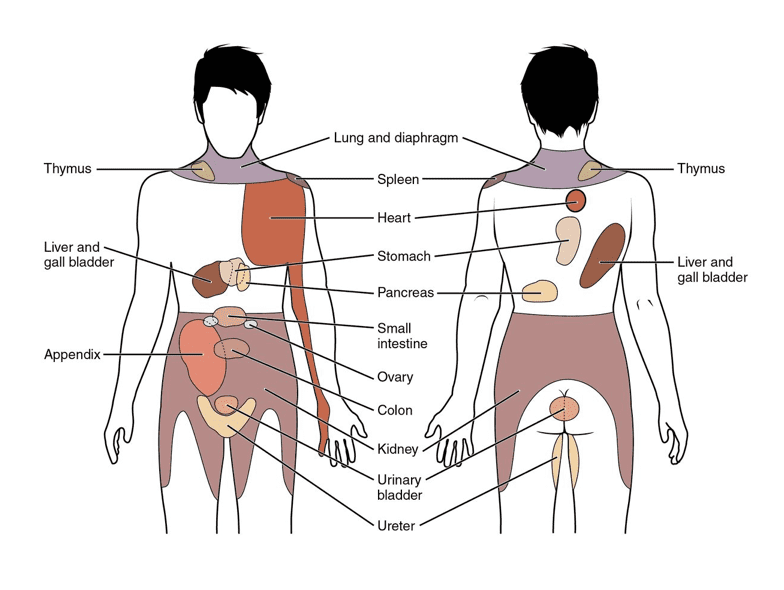

And of course there is visceral referred pain. Visceral referred pain may masquerade as somatic referred pain known as viscerosomatic convergence. It is often associated with autonomic phenomena, including pallor profuse sweating, nausea, GI disturbances and changes in body temperature, blood pressure and heart rate (Procacci P 1984).

It is important to remember that noxious sensory information from the periphery is nociception and NOT pain. Pain is when the brain is gathering all of the available information and interpreting this based on sensory input, previous experience, context, psychological factors, social environment etc This is why a pain experience can vary significantly from one person to another not only in location but also in intensity.

Referred pain patterns may not always map perfectly to these pictures and they will not provide you with a cause of the pain, It can however be used as a guide to which spinal segment may be involved. A thorough subjective and objective examination is always key.