Reconceptualising pain with a plastic brain

Can your brain change?

Have you every changed your mind, or changed your opinion? Even when you believed something so strongly, but you were still able to change. What about that bad habit that you were able to shake?

Have you ever tried to learn to play an instrument, learn a new language or take up a new sport?

You were probably bad at the start, but with time and practice you improved. These are examples of your brain changing.

What about chronic pain? Are you stuck with that forever or can that also change?

The brain is highly plastic, and it CAN change given the right environment and input. It’s not always easy, but it’s possible.

The brain was once thought of as a fixed structure, and you are the way you are and that’s it. However, we know this now to be a neuromyth. The brain is malleable and will continue to change until the day we die, and our experiences will shape who we are.

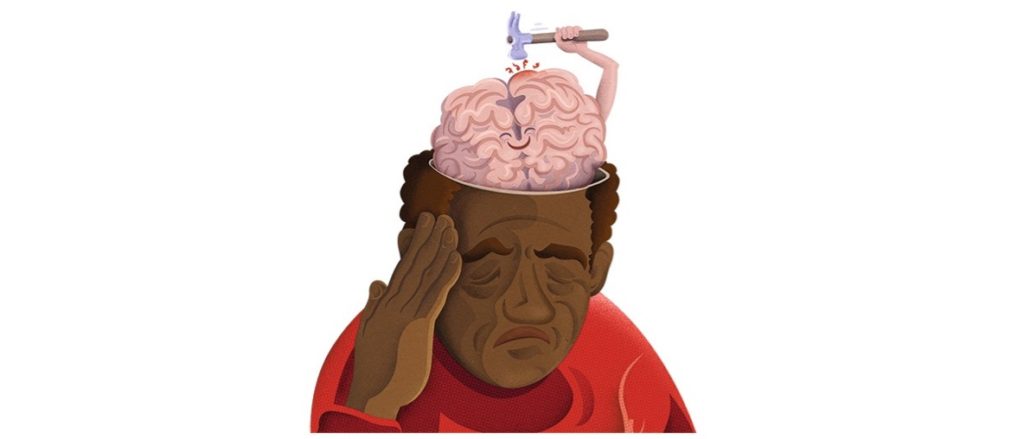

Let’s take a look at some of the negative implications of brain plasticity. Chronic pain is often thought to be an issue in the tissues, and while this can certainly be a contributor, the long-term implications of chronic pain cause structural and functional changes to occur in the brain. This affects cognitive function, emotion, and behaviour.

Pain is much more than physical problem…

Pain is a construct of experience, predictions, emotions, expectations, thought, beliefs, sensory input, and multiple other social and environmental factors. This multifactorial stew of different factors can lead to negative neuroplastic changes in the brain.

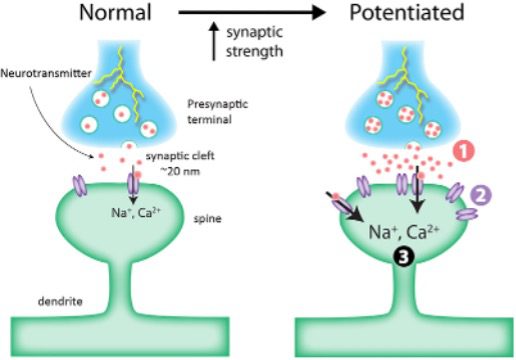

You might be familiar with the idea that the more your repeat something the better you get at it right? “Practice makes permanent”.

The neuroscientific word for this is Long-term potentiation (LTP) this is essentially the repeated activation of neural networks that can lead to improved efficiency of the nervous system. This LTP does not discriminate negative vs positive changes.

magine a day in the life of a chronic pain patient, where their pain becomes the centre of attention and their whole life and focus revolves around that pain experience, it can dictate their mood, how much activity they perform, how much they sleep, how much they work and socialise, among numerous other factors. This can potentially become a part of who they are.

Their belief system, emotions behaviour, social support network, coping mechanisms level of self-efficacy are all associated with a pain experience. The longer this persists it can become an entangled mess of a multiple factors that cause long term potentiation, improved synaptic efficiency and neoplastic changes.

Pain is a learned response…

You learn from an early age not to touch a hot stove, right? That is helpful, without learning that, touching a hot stove is dangerous it could lead to serious injury. However sometimes our perception of what is dangerous can become skewed due to our previous experience and beliefs.

Meet John, he sprained his ankle playing soccer, his ankle is swollen so he walks with a limp, this is helpful in the short term. This is a protective mechanism to avoid further injury to damage. However, if John continued to walk with a limp after the tissue has healed this would be unhelpful and this would me maladaptive. Also, if he believed that soccer was very dangerous because of this painful experience, he may be avoidant of playing again.

Now, John believes his ankle is still damaged. He has poor expectations of recovery, so he has been resting it because he is worried that if he runs, he will make it worse. He withdraws from playing soccer with his friends which impacts his social connection, this upsets him as soccer was a great opportunity to socialise and a great stress release for him. John is now worried that he will need surgery. This is a common spiral in chronic pain suffers.

We can see how there may be a physical trigger that causes pain, however there are multiple factors that can influence a pain experience. And therefore, pessimistic attitude, negative thoughts, avoidant behaviours, stress, and worry can cause negative neuroplastic changes in the brain, and even after the tissue has healed, the pain still persists. And just like trying to learn something new, repeated activity if these neural circuits can lead to structural and functional changes to the nervous system, this is a classic example of the brain changing.

“Thoughts can change our brains.” Norman Doidge

So, if you can develop chronic pain, that is evidence that the brain can change right?!

Take the example of a gangrenous foot, this is damaged tissue, that can be extremely painful. Amputation of the leg should completely remove pain; however, patients may suffer from phantom limb pain.

Why is this?

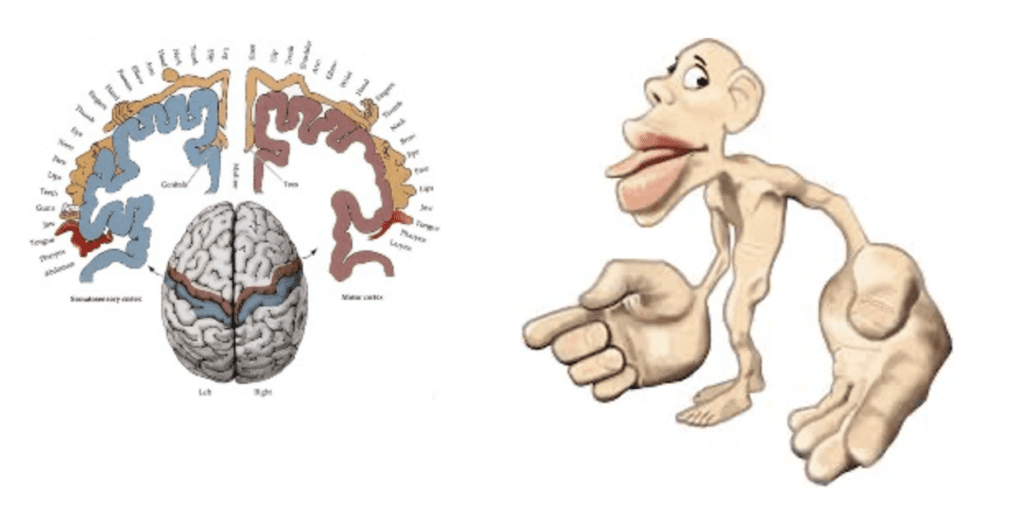

Well, although the site of pathology has been removed there is still a cortical representation of that body region and therefore the brain still perceives sensation and pain in that area of the body even though the physical limb is no longer there.

In patients with chronic pain, cortical smudging may occur where the area in the brain mapped to an area in the body can merge / smudge with another area in the cortex and therefore having a much larger representation in the cortex. Consider chronic low back pain, it is often hard to locate the specific site of pain (Non-specific LBP), and the longer pain persists the area of pain may spread it may be felt across the back, buttock and even into the legs. This is not usually linked to increasing tissue damage, rather it is due to neuroplastic changes in the brain.

Imagine having an itch in your knee that you can’t scratch, or a pain that you can’t rub on for relief. Would you feel irritable, frustrated, uncomfortable, annoyed, distracted, or angry? These are all responses that are felt in chronic pain sufferers and although it may be perceive this is a tissue-based problem scratching it, rubbing it, pressing it or even surgery may not relieve symptoms, because the change has occurred in the brain.

The good news is that the brain is changeable and the brain can be re-mapped.

It may be quite inspiring and empowering to look at chronic pain in this light, with less focus on the tissue or pathology and understand the changes in the brain that have occurred.

By promoting resilience, optimism, safety, confidence, movement, and positive coping strategies we can help people to rewire their brains through positive thoughts and emotions, and exercise that can break the cycle of chronic pain and assist with cortical remapping.

Remember back to John, how he became avoidant of movement. Well, this can lead to deconditioning of the limb but also changes to the brain.

(Remember that the right side of our cortex controls the left side of our body, and the left side of our cortex controls the right side of our body.)

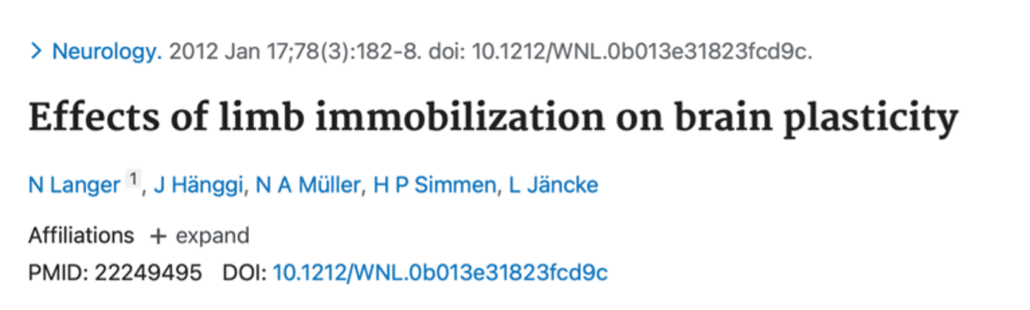

In this study by Langer et al. (2012) they examined 10 right-handed subjects with injury of the right upper extremity that required at least 14 days of limb immobilization. Subject underwent MRI at the start and end of the trial. They measured cortical thickness of sensorimotor regions and fractional anisotropy of the corticospinal tracts.

They found that immobilisation or the right upper extremity led to a decrease in cortical thickness in the left primary motor and somatosensory area as well as a decrease in FA in the left corticospinal tract.

They also found that the motor skill of the (non-injured) hand improved and is related to increased cortical thickness and FA in the right motor cortex. Perhaps due to the increased use and improved synaptic efficiency.

Therefore, immobilisation after only 14 days created changes in the brain. Imagine the long-term effects of immobilisation, avoidant behaviours or learned non-use.

If you don’t use it, you lose it.

This is a great example that the brain can change and also, reasoning for why we should promote movement and exercise as an early intervention for acute and chronic pain.

Although the focus of this article is on the brain, this is not the only factor involved in pain and we need to appreciate how the combination of biological, psychological and social factors can contribute to pain. Due to the multifactorial nature of pain we need to look at the whole person and not just focus on one factor.