An update on Plantar Fasciitis

In practice, and conversations with friends, one of the most common presentations that I hear is plantar fasciitis. This seems to be affecting most people that have pain in their foot and just like pain down the back of the leg being over-labelled as sciatica, it’s usually reported as ‘the same issue that my uncle’s, 2nd cousin’s, wife had forever, so I think that’s what I have’.

We need to have the knowledge to be able to address that self-diagnosis, and consider what may be relevant to their presentation, to then be able to address most of the factors contributing to the above situation.

So, let’s have a quick look at plantar fasciitis first, and what we should consider when presented with plantar foot pain –

Firstly, we should be using the title, Plantar Fasciosis, as it is not a primary inflammatory condition of the plantar fascia (PF) (which is what an -itis indicates), it’s a degenerative pathology of the PF, where it can become roughly twice as thick as non-degenerative PF.

It may not be as common as what you think for foot pain presentations, with approximately 15% of plantar foot pain being attributed to plantar fasciosis.

Various types of ultrasound (US) imaging are used as the standard for diagnosis, with different techniques being able to detect positive findings where patients had negative US results as well. It can be important to use this in management if there is non-responsive, or ongoing presentations to be able to accurately diagnose.

For any presentation, the risk factors for the condition are important for us to be aware of, so let’s highlight some of those below –

Heel spurs are very commonly noted in patients with plantar fasciosis, which we may considered as a predisposition to the condition.

Increased BMI was found to be an associative risk factor in non-athletic populations, but not in the athletic population. Interestingly, there were common findings of weaker muscles responsible for hallux and lesser toe plantar flexion, ankle dorsiflexion, inversion, eversion, as well as smaller muscle mass of the foot in individuals experiencing plantar fasciosis.

What this might indicate for us is that increased BMI is not exactly a risk factor if there is relative strength and capacity of these tissues from the individual regularly training.

Increased age, weight bearing activities (including walking and standing), and increased plantarflexion ROM had weak evidence of being risks, and other factors that are commonly considered, whose links are questionable, are running kinematics and ground reaction forces, as well as calf muscle endurance. This means that we don’t have as clear of a view on risks as what many of us might have thought.

When we have a patient that presents to us in clinic with foot pain, recognising the signs and symptoms of plantar fasciosis is a good start for us to consider –

Pain in the inferomedial surface of the heel is the typical location of pain and this is often exacerbated by both weight bearing and non-weight bearing activities. It can resolve after a minimal-moderate amount of exercise, and then aggravated again if continuing further. Periods of rest can also aggravate symptoms of plantar fasciosis.

In the chronic population, it is slightly more common for pain on the lateral border of the foot to be reported than the acute stages and this has been suggested to be attributed to the change in gait due to the more commonly reported medial heel pain.

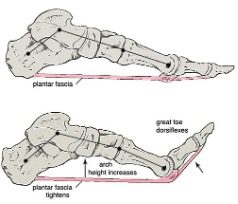

Positive signs are often indicated when palpating the medial calcaneal tuberosity and performing the Windlass/Jack test of passive dorsiflexion at the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

These are of course noted along with the above-mentioned functional insufficiencies in the foot and ankle muscle groups.

And there is of course differential diagnosis that we need to rule in or out and depending on what equipment and training you have available, there’s a good chance that some of these will need to be referred on. Before we cover these though, you need to consider what the likelihood of these occurring are. If the pain has had a gradual onset, no known conditions causing lower bone mineral density, with no trauma to the area and no changes in loading, it would be unnecessary to consider a fracture as likely, for example.

Contusion of the calcaneus, the calcaneal fat pad and surrounding soft tissue are a common differential to consider. This is usually best noted with thorough history of the patient’s complaint. Stress fractures are also to be considered if there is a relevant mechanism of injury, significant increases in training or surfaces, load and intensity, or risk factors such as osteopenia and porosis.

Neuropathic pain should also be considered with tarsal tunnel syndrome a possible differential, and a patient’s pain may be residual to one of these causing neurogenic inflammation, which we should consider both peripherally and centrally.

And as we mentioned earlier, heel spurs are a consideration as well as a potential risk factor to developing plantar fasciosis, but we can also consider if there is a lacking capacity of muscles originating from the medial surface of the calcaneus, that these may be prone to degenerative change themselves.

Of course, knowing how to assess, treat and manage plantar fasciosis and the above differentials is important, but at least having an update on the understanding of it is a great start for us to be able to help educate our patients, and more appropriately manage their presentations.