Palpation in practice

Palpation is a largely utilised tool among health professions. Often relied upon for assessing pain provocation, making a diagnosis, or of course, modality application. Generalising some commentary that I’ve often heard in clinics, classrooms, and online, assessing specific joint movement is often encouraged to improve with experience, and be the catalyst for more effective outcomes.

Most clinicians see these assessments to be important. Abbott et al., (2007), surveyed 466 physical therapists of the USA and New Zealand, finding that 66% believed passive accessory intervertebral motion tests were valid for assessing quantity of segmental motion, and 76% believed the same for passive physiological intervertebral motion tests.

Even though we’ll be questioning the validity of motion-based assessment, this should still be a consideration for clinicians, alongside pathomechanical and biopsychosocial understandings made more common since 2007.

When assessing joint related movement, we have two different types including arthrokinematic movement and osteokinematic movement.

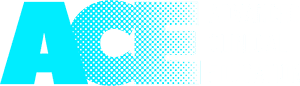

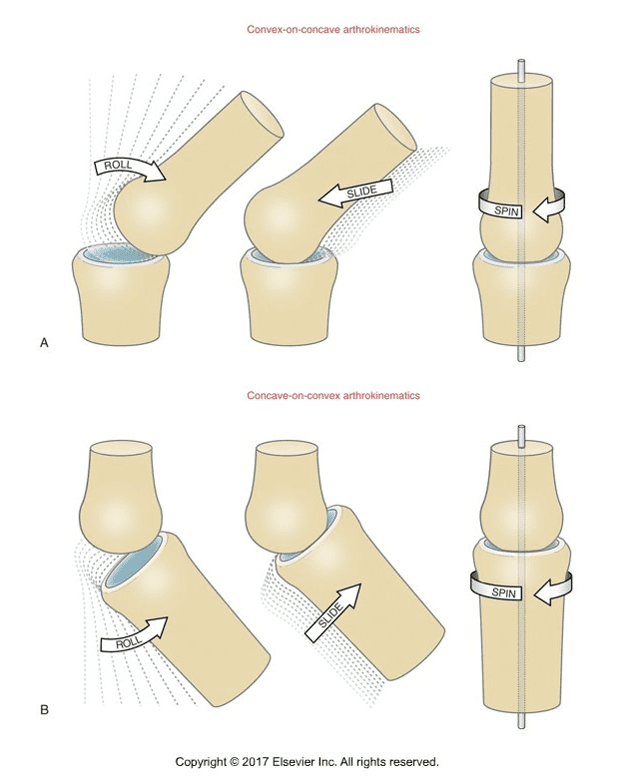

Arthrokinematics, being the specific motion between articular surfaces. This is also referred to as accessorymovement and cannot be performed by an individual actively. These movements are a roll, slide, or spin of articular surfaces, such as the tibia rolling anteriorly and externally rotating when completing knee extension.

Osteokinematic movement is movement of a body part that can be completed actively. This is also called physiological or gross movement. Knee flexion or extension is osteokinematic and requires arthrokinematic movements to be completed.

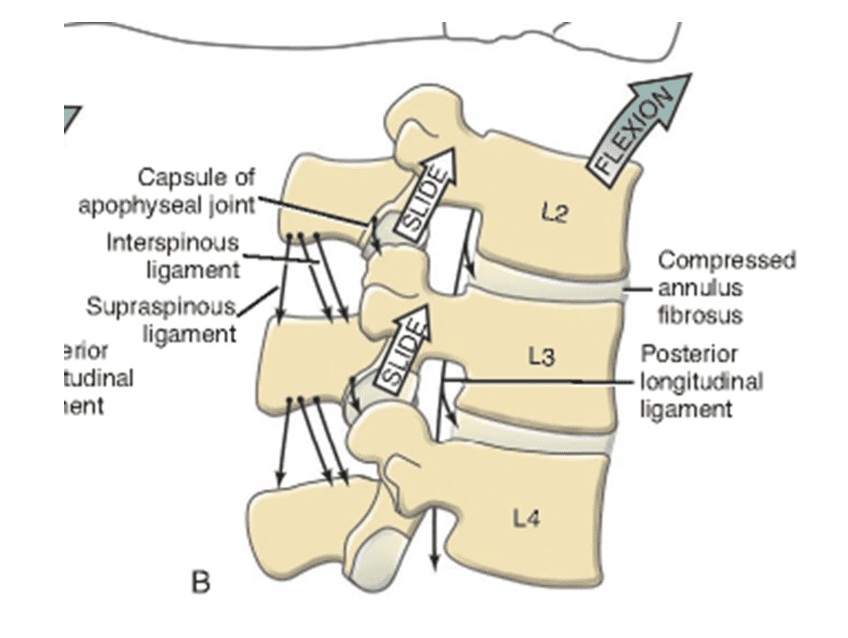

In the spine, the inferior articular facet of the superior vertebra slides superior and slightly anterior of the vertebra below during trunk flexion.

Osteokinematic movement is more easily assessed for quantity and quality in clinic, whilst it’s often encouraged through training and mentoring that palpation of arthrokinematic motion, such as joint mobilisations, will come with time and experience. But in attempting to assess these movements with certainty, questions are raised about our findings.

If we start with the difficulties of a static assessment, there is commonly more disagreement for bony landmark and soft tissue palpation between examiners.

In a literature review of 9 articles by Stovall & Kumar (2011), a total of 209 subjects were assessed by 51 evaluators (both post-grad clinicians and students). The findings showed that there was a poor agreement of palpating sacroiliac landmarks between evaluators.

Nolet et al., (2021), completed a systematic review of the validity and reliability when assessing soft tissue structures, bony anatomy, and joint mobility for subjects with lower back pain. Again, it was found that there were poor levels of agreeability between raters when performing the examinations in these articles. Some assessments were able to provide greater reliability, such as palpation of the sciatic nerve in the ischiofemoral space and gluteal trigger point palpation. Whilst these yielded more agreeability between examiners, the validity of these examinations still requires further investigation. However, motion-based assessments utilising palpation such as Gillet’s test, and trunk flexion and extension both seated and standing, did not have this level of reliability in their systematic review (Nolet et al., 2021).

Rezvani et al., 2012, also demonstrated poor reflection of lumbar spine motion in Schober, and modified Schober tests when compared to radiograph imaging. This is despite having much better intra and interrater reliability between examiners than other articles have shown for motion-based assessments.

This may not come as a surprise to many. Even when we can have more reliable results between clinicians, we may still expect poor validity. There are several limitations to this, including the several layers of different tissue when palpating. A depth of 3-6cms or more from the skin to the facet joints and transverse processes of the lumbar spine, dependant on the individual and the lumbar segment in question. And various experience and techniques of palpation-based assessment. All of this will impact our ability to claim a certain outcome of our manual intervention or exam.

To circle back to the start though, this doesn’t mean that we should disregard these forms of assessments and manual therapy techniques. For example, when we are using joint mobilisations of a vertebrae in practice, instead of aiming to make a confident claim of the degree of mobility and specific vertebra targeted, we may be better having a perspective shift to what the patients’ experience is. These techniques can still provide us with subjective information from our patients, which we then utilise with our clinical reasoning and treatment and reassess for improvements.

Accepting these limitations shouldn’t change how we perform in clinical practice, rather, it should inform our acknowledgment and communication of these findings from making direct claims to using them in an updated model in clinical practice.