Pain and performance

Let’s consider a high-performance athlete.

For an athlete to perform at the highest level, they need to put in the work, they need to train, they need to eat well, they need to sleep, they need to ensure they are focused on a goal, and they need to minimise distractions that may stop them from achieving their goal. Athletes treat their body with respect, but you don’t need to be an athlete to respect your body.

If you are a sprinter, the stopwatch doesn’t lie. You either run faster or you don’t. In the gym, the weights don’t lie… You either lifted a heavier weight or you didn’t. You either did more repetitions, or you didn’t… You get the idea.

I will ask the question…Is this way of thinking different to modulating and recovering from pain?

In the context of pain, we could reflect on encounters with patients and ask… Did you put in the required effort to make change? Did you attempt to modify variables over an extended period of time or didn’t you?

I know pain is more complex than simple cause and effect but… Let’s simplify it for a moment.

In the context of strength training, the weights don’t get lighter, you get stronger, you increase tissue capacity, metabolic capacity and neural adaptations occur etc. Does that mean strength training gets easy? Obviously not, because, if it’s easy, the stimulus is likely inadequate. You get out what you put in.

An athlete will rarely say they had an easy session unless it was programmed to be an easy session.

With both pain and performance, it’s all about modifying variables. This is the importance of a coach. An athlete without a coach is less likely to see progressions in performance at any level, but the athlete’s performance is not the sole responsibility of the coach. Just like pain relief and rehab is not the sole responsibility of the clinician. It’s a 2-way street.

A coach assists the athlete in applying the appropriate stimulus, creating the right environment, allowing the appropriate time for recovery and adaptation along with the right advice and support. The coach can’t show up to the gym for the athlete, the coach can’t do the reps for the athlete, the coach can’t coach make the athlete sleep and eat the right foods etc.

Clinician don’t fix injuries in the same way that coaches don’t make athlete win races. But without the coaching and guidance athletes may be less likely to get optimal results. How many athletes were self-coached at the most recent Olympics? And how many athletes have won gold medals or world titles with no coach?

I guess my point here, is that we don’t see the coach on the podium with a gold medal around their neck. They play a big role, but they can only do so much.

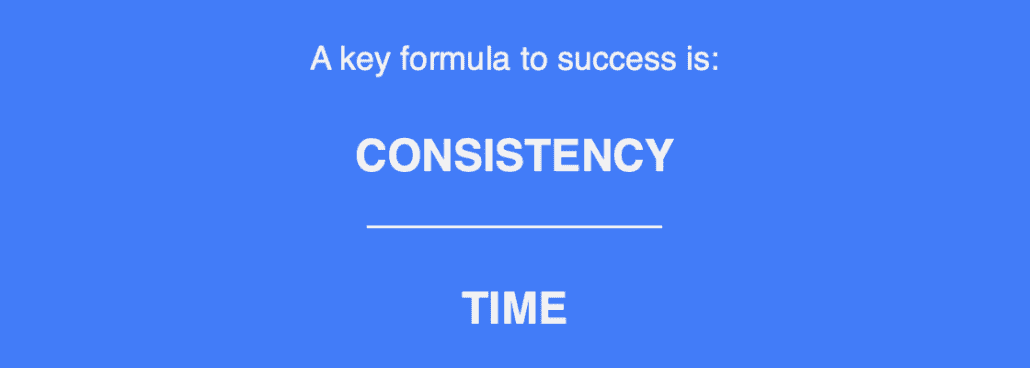

You can apply this formula to anything… Education, building a business, building a client base, nutrition, sports performance, injury/pain rehabilitation, etc.

In the context of chronic pain, we don’t need fancy tools, recipes, or protocols. Much of the changes can occur by modifying key contributors including psychological, behavioural and lifestyle factors. In clinical practice, we, as clinicians are just like coaches, it is our job to educate, support and advise. We cannot take on the sole responsibility of ‘making the change’ or ‘fixing’ the patient.

I think this is a fitting joke to finish with…

How many psychologists does it take to change a lightbulb?

One, but the lightbulb has to want to change.

Pain is multifactorial and we know there are often significant behavioural and lifestyle contributors to a pain experience. These are changes that can only be made by the patient. Creating an environment where the multifactorial nature of human physiology is consistently accounted for over a long period of time will do wonders to improve the homeostatic balance of the incredibly complex human body. Making positive long-term changes are a step in the right direction to allow the body to be a robust healing machine.

In both pain and performance, human physiology must be respected.