Demonising the tilt: Is pelvic posture misconceived and misinterpreted?

I’ve been told I have back pain because I have an anterior pelvic tilt…

Is there really a causal relationship between pelvic tilt and pain?

Let’s start this with an example…

2 patients walk into a clinic. The first one has low back pain and then the therapist notices that they have what looks like an anterior pelvic tilt, and the therapist thinks AH HAH! That’s it! It’s because of your anterior tilt…that’s the cause of your pain, if we fix that your pain will go away.

The second patient walks into the clinic with an anterior pelvic tilt but with no back pain, and it is pointed out to them that, they need to “correct that pelvic tilt” or you will have pain one day. (As if there is something wrong with him) And then any minor pain that may come about in the future for what ever combination of reasons, “HA told ya so… it was only a matter of time…you should have corrected that pelvic tilt”

Patient 1 eventually gets frustrated with not being able to change his pelvic tilt and also the fact that their pain did not go away made him feel helpless.

Patient 2 leaves feeling anxious and stressed about the possibility of eventually getting back pain and becomes more vigilant, guarded with movement and concerned with ‘alignment’.

This mechanical labelling can strongly influence behaviours and beliefs.

Let me ask you some questions to get you thinking…

How do you know that it is a true anterior (or posterior) pelvic tilt?

▶️ How is a pelvic tilt measured?

▶️ Is it by simply standing back and looking or kneeling down and palpating ASIS and PSIS and lining up the 2 points with your line of vision?

▶️ What are the normative values?

▶️ Is it 1 degree, 5 degrees, 10 degrees, 30 degrees?

▶️ If they had the same pelvic tilt and been pain free their whole life, before the onset of symptoms, could we confidently say that a pelvic tilt is the cause of pain or that it needs correcting? Or that the pelvis was more neutral the pain would not have started?

▶️ Why do people with anterior and posterior pelvic tilts NOT have pain also?

▶️ What other factors may influence pelvic position?

▶️ Are we all the same shape and size?

▶️ What about morphological variation?

Ok that’s enough questions for now…

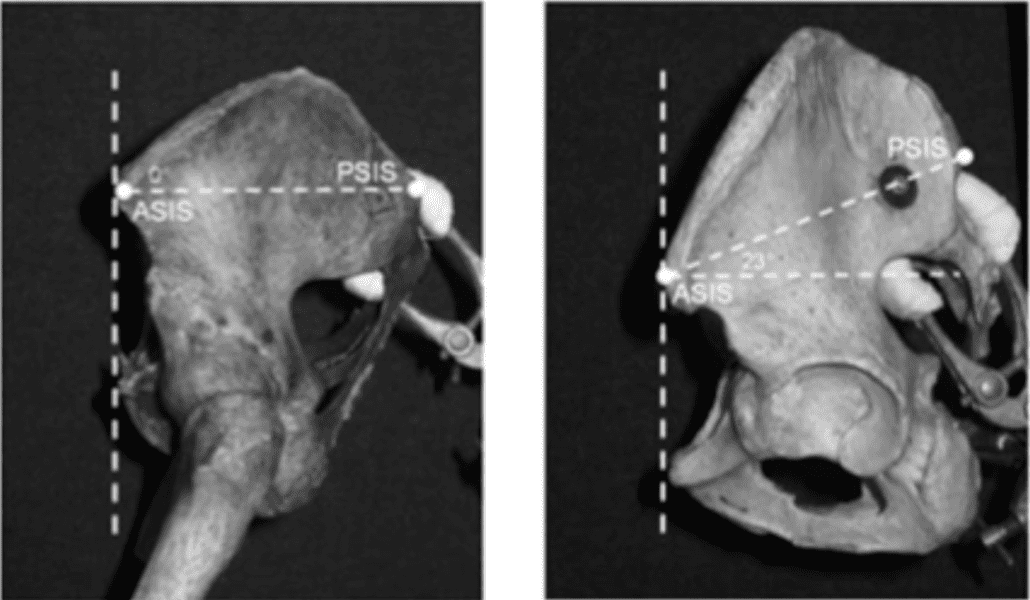

A study by Preece et al examined the variation in pelvic morphology in 30 cadavers and found the ASIS – PSIS angle varied between 0-23 degrees with a mean 13 degrees of standard deviation.

If this angle is significantly influenced by morphological variation, then it may not be possible to correctly identify anterior pelvic tilt.

The large standard deviation in this measurement demonstrates the large variability in asymmetry across the different specimens. (Preece et al 2008).

Preece also found that there can be side to side differences in morphology (ASIS – PSIS angle) giving the appearance of an innominate rotation.

Acetabulofemoral joint morphology can also influence pelvic angle (DeVries Z et al (2021)

By labelling pelvic tilt as the reason for pain can be disempowering when they are unable to change it and frustrated when symptoms persist, this can lead to increased emotional distress and helplessness in chronic pain presentations. It also provides a simplistic mechanical explanation for pain as a linear cause and effect relationship.

I’m sure many of you can think of a patient who tells you what postural ailment they have… “I’ve got an anterior tilt and a twisted L5” And they have held on to this belief for many years just because someone once told them…

Darlow et al found that what clinicians / health care professionals say had the strongest influence on upon patients’ attitudes and beliefs and information and advice provided could influence the beliefs of the patients for many years. The influence of linking a postural variation as a cause of pain may influence beliefs and serve as a barrier to recovery in the long term.

Our understanding of pain and LBP has evolved over the years and is steering away from a specific tissue based / structural cause of pain. Hence the term non-specific low back pain. This occurs in 90% of cases where there is no known pathomechanical diagnosis that can be linked to the cause of pain. LBP is multifactorial and simply labelling a specific posture or pelvic position to have a causal relationship with pain is 1 dimensional.

Mechanical damage / injury also does not always correlate with pain. There is a poor association between pathological MRI findings and pain and there is a high prevalence of Asymptomatic findings on imaging. The same goes for having a poor correlation with spinal and pelvic postures.

Is the anterior tilt a cause for pain or is it an incidental finding when someone presents with pain?

You might say but “An anterior tilt increases lumbar lordosis and increased compression in the spine” or “I often see pelvic and spinal postures correlated with people who sit all day.”

Yes, there are people who sit all day who often present with low back pain, but is it the posture or the sedentary lifestyle or both? Sedentary behaviour is a risk factor for LBP. (Along with the other factors that come with a sedentary lifestyle) Simply focusing on changing pelvis position is unlikely to influence behavioural change and address the multifactorial nature of chronic pain.

Swain et al. conducted a systematic review of systematic reviews and all 7 systematic reviews found no causal relationship between sitting and LBP…therefore it is more than just sitting that that may be linked to increased risk of LBP. Lifestyle and behaviours need to be considered.

A meta analysis of 8 studies showed no difference in lumbar lordosis angle in people with LBP and those without LBP (Laird, R.A., et al 2014)

There is evidence that people with low back pain may find certain postures provocative, however it cannot be concluded that postures are the cause of pain” Dankaerts W (2009), Slater D et al. (2019).

Where did these beliefs come from?

The societal and media influence that has been drilled into us from a young age in the classroom and at home right through to work place health and safety training, the fitness industry, friends, family and your family GP.

The message to sit up straight, bend your knees when you lift and maintain alignment though your hips and spine. Avoiding anterior or posterior pelvic tilt, avoiding arching the back when lifting, as this can be a cause for back pain…

This has been further instilled in patients via health care practitioners spotlighting structural alignment and demonising asymmetries and subtle variations in joint positions.

Many undergraduate programs that we all completed have emphasised posture and structural alignment. It was one of the first things that many of us learned. I remember standing at the front on my class in my underwear and the whole class picked on every little asymmetry that didn’t fit a ‘perfect anatomical posture’, afterward I felt anxious like I needed ‘fixing’ as if I had something wrong with me and reliant on someone else correcting me… (I know…poor me).

Postural ‘correction’, and ‘corrective’ exercise to restore alignment was a big part of the way that I treated in the first half of my career. (I’m sorry to all of my patients whose feelings I hurt… Seriously!) It was simplistic and ignorant.

What is the problem with this?

Being told that you must sit or stand in a certain way can promote guarding and protective behaviours. Furthermore, if a patient is presenting for treatment and we are pointing out subtle asymmetries and suggesting “postural correction” it may be interpreted as is there is something wrong with them. Perhaps we should be looking at what is ‘normal’ for that individual person and not is what is believed to be ‘text book’ normal.

Barker et al found that patients often interpret terminology differently to what health care practitioners intended and different medical and anatomical terms were misconstrued, and misinterpreted which had inadvertent negative connotations or implications.

So does pelvic position and spinal posture really matter?

There are certainly times that we can educate a patient on a better way to sit or stand that may change their symptoms.

Posture should be dynamic and variable. Not fixed and rigid.

Posture is just 1 factor with multiple other variables, and we should not spotlight variations in pelvic positions or spinal posture as a cause of pain, as we know it could be a completely normal morphology for that person.

If there is a mechanical cause ie after sitting in a slumped position for a few hours I start to feel some pain and then sitting in an extended position immediately reduces it then that’s an easy one… educate them on variability.

As I write this I’m sitting on the plane on a 5 hour flight in the middle seat in the most upright straight spine position with my elbows tucked in to my sides trying to avoid awkward contact with the 2 massive blokes sitting next to me, and my lower back is screaming at me, but it’s not because of my anterior tilt…

Certain positions may place more stress on musculoskeletal and neural structures. But do we really need to “correct” and anterior tilt or an elevated shoulder or scoliosis? Is it even possible? Is it normal? or your interpretation or ‘abnormal’

In the chronic pain patient often it’s much more complex then mechanical force of a ‘tight hip flexor’, what about bone and joint morphology, shape, length, angle etc.

Let’s consider some other factors…

Posture may be a reflection of mood. There is a correlation with depression and anxiety disorders and chronic pain. People with these disorders are more likely to experience more severe pain than those without mood and emotional related disorders. Furthermore people who are in chronic pain are more likely to have depression and anxiety disorders. Depression is also associated worse outcomes long-term in chronic pain suffers.

When considering any pain experience there are significant influences from the combination of biological, psychological, social and environment factors that need to be understood. A persons mood, level of stress, anxiety etc can all influence their pain experience. Depression and emotional distress can both predict the onset of first time LBP (Jarvik et al. 2005).

Let me ask you another question…

Is the cause of someone’s LBP pain from standing in an anterior tilt at work all day OR what about their job satisfaction, work environment, level of stress at work, financial stress, social engagement, amount of sleep, family circumstances, current level of exercise, nutritional factors, alcohol consumption, medications, co-morbidities…

Posture is easy to see and easy to point the finger at, but mental health disorders are not and these are closely related with chronic pain. Perhaps posture can be useful to allow us an insight to explore other psychological and emotional contributing factors?

All of these factors may contribute, we cannot simply label ONE as the cause.

Now I know this may go against many people’s beliefs systems as postural assessment and postural correction has been at the forefront of what many practitioners have built their business on and treatment style around. I am not saying that posture is not a factor, what I am saying is that we shouldn’t be fitting people into a “textbook norm” and spotlighting posture as the cause of their pain and the focus of the treatment. There are significant variations in bony morphology and genetic makeup and by reinforcing that posture is the cause of pain or that it may lead to pain in the future is just not supported in the literature. It can also strongly influence a patient’s beliefs and may be a barrier to recovery.

What should we do?

Educate patients about the normality of different postures, promote safety in different positions, movements, and postures. Address negative beliefs around posture, consider lifestyle, environmental, social and psychological factors.

Perhaps we have got it wrong with ideal ergonomic work set ups and perfect lifting techniques focused on lumbopelvic alignment and symmetry. We are all unique different body shapes and sizes with differences in anatomical makeup. Why are we adjusting the body position to fit ‘ideal’ or instructing so called perfect lifting mechanics with everyday movement? Should we consider adjusting work set ups and tailoring lifting styles to suit the person, rather than changing the person to suit the standard text book biomechanical perfect? Pavlova, A et al (2018).

Yours in Health,

Bodine Ledden

References

Barker KL, Reid M, Minns Lowe CJ. Divided by a lack of common language? A qualitative study exploring the use of language by health professionals treating back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009 Oct 5;10:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-123. PMID: 19804629; PMCID: PMC2765953.

Dankaerts W, O’Sullivan P, Burnett A, Straker L, Davey P, Gupta R. Discriminating healthy controls and two clinical subgroups of nonspecific chronic low back pain patients using trunk muscle activa- tion and lumbosacral kinematics of postures and movements: a statistical classification model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1610-1618. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181aa6175

DeVries Z, Speirs AD, Salih S, Beaulé PE, Witt J, Grammatopoulos G. Acetabular Morphology and Spinopelvic Characteristics: What Predominantly Determines Functional Acetabular Version? Orthop J Sports Med. 2021 Oct 22;9(10):23259671211030495. doi: 10.1177/23259671211030495. PMID: 34708135; PMCID: PMC8543727.

Jarvik JG, Hollingworth W, Heagerty PJ, Haynor DR, Boyko EJ, Deyo RA. Three-year incidence of low back pain in an initially asymptomatic cohort: clinical and imaging risk factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005 Jul 1;30(13):1541-8; discussion 1549. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000167536.60002.87. PMID: 15990670.

Pavlova AV, Meakin JR, Cooper K, Barr RJ, Aspden RM. Variation in lifting kinematics related to individual intrinsic lumbar curvature: an investigation in healthy adults. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018 Jul 15;4(1):e000374. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000374. PMID: 30057776; PMCID: PMC6059291.

Preece SJ, Willan P, Nester CJ, Graham-Smith P, Herrington L, Bowker P. Variation in pelvic morphology may prevent the identification of anterior pelvic tilt. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(2):113-7. doi: 10.1179/106698108790818459. PMID: 19119397; PMCID: PMC2565125.

Slater D, Korakakis V, O’Sullivan P, Nolan D, O’Sullivan K. “Sit Up Straight”: Time to Re-evaluate. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019 Aug;49(8):562-564. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2019.0610. PMID: 31366294.

Swain CTV, Pan F, Owen PJ, Schmidt H, Belavy DL. No consensus on causality of spine postures or physical exposure and low back pain: A systematic review of systematic reviews. J Biomech. 2020 Mar 26;102:109312. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.08.006. Epub 2019 Aug 13. PMID: 31451200.

Laird, R.A., Gilbert, J., Kent, P., et al. Comparing lumbo-pelvic kinematics in people with and without back pain: A systematic review and Meta analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15, 229 (2014)