Questioning The Concerns Of Degenerative Disc Disease

Degenerative disc disease (DDD)…

The name alone sounds like it should be feared, let alone the descriptions, stories, information and advice that we often hear along with the name.

I’ve seen a lot of patients with DDD and I was initially worried in the earlier part of my career anytime it was mentioned in a consultation.

I was worried about how fragile their spine and back might be, not sure what advice to provide for something so severe, and I was lost in which direction the consultation with patients should go.

This was heavily influenced by the stories that patients shared when they had the scans, and what I was hearing from other professionals –

“Your back is s*#t!” One patient shared with me of what their doctor said… who was just wanting to be open and honest with them.

“We need to have scans before treating you in case we find things like degenerative disc disease.” From therapists trying to show good intentions for their patients…

“I just have to learn to live with the pain because there’s nothing we can do about it.” From a patient who had lost hope.

I’m sure you’ve heard similar sentiments in your clinical practice and had just as many patients with DDD as I have. It’s no wonder that this is the case when we look at the likelihood of the population experiencing it –

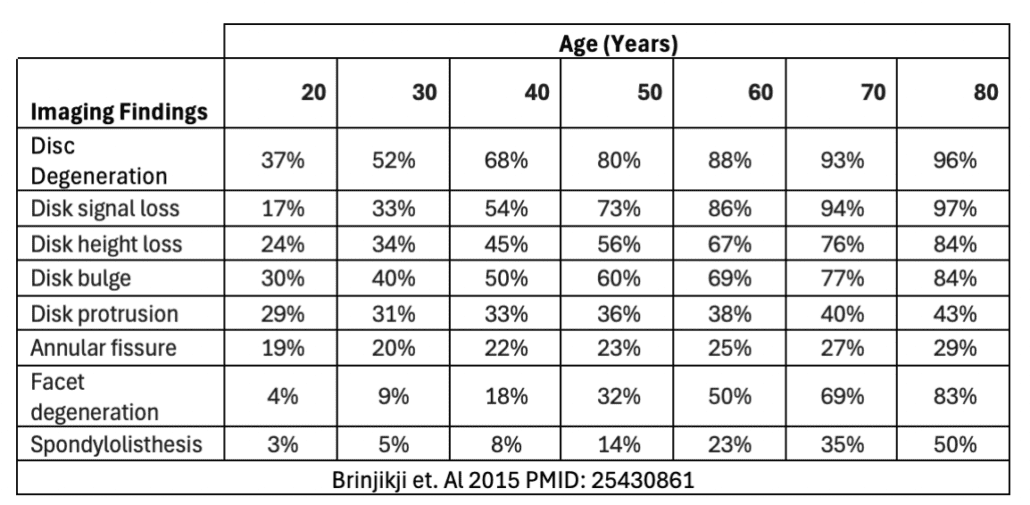

DDD is a term used to describe degeneration of the spine in a very broad sense. This includes the imaging findings listed above and others such as foraminal or central stenosis. We can see just how common it is, and it makes sense that we see it so much in our clinical practice.

What is even more shocking than how prevalent it is in imaging – is that these are findings of an asymptomatic population!

A systematic review of 33 articles with imaging findings of 3110 adults who were not experiencing any back pain provided the results of the table above. Further to that, studies were only included if the participants had reported

no history of back pain, excluding any that didn’t explicitly state that the participants were pain free or who had had even low to mild back pain in the past – providing very strong evidence that the high incidence of DDD in the general population does not have a strong correlation to the rates of back pain.

Something that many of you will be aware of, is that pain is multifactorial – we can’t always pinpoint a singular ‘root cause’ to explain its presence, as we’ve discussed in previous articles.

The likelihood of something that can be found in imaging, such as DDD, to be the cause of a lower back pain, something about 80% of the population will experience in their life, is something that we need to question.

We need to ask –

➡️ How long have these findings been present before they’ve experienced their back pain?

➡️ If DDD has been present the whole time, why has their pain been episodic or only just recently occurred?

➡️ Why can we see long term improvements in conditions, without changing the degeneration?

➡️ If these findings were present before their pain, what else has changed since they’ve become symptomatic?

➡️ Will getting imaging to reveal something that is most likely present, even whilst they were living a healthy and active life, really change my treatment plan?

Degenerative Disc Disease can seem a scary name for something that is what we should expect to see in everyone as a natural and normal change in the human body – just as we would expect to see a body with wrinkles and scars from a life of activity.

There are cases of DDD that most definitely relate to a patient’s pain presentation, but with over a third of 20-year-olds having asymptomatic DDD, and only increasing exponentially with age, it is more likely that other factors such as sudden falls and injuries, lifestyle, poor load and activity adaptation, or sensitisation of other structures could be the major contributor to our patient’s pain.

The fact that these findings are present with and without pain, means that we don’t need to be frightened of movement and activity whilst in a painful episode, rather, we only need to adapt activity to have a tolerable experience.

We should be able to confidently put the fear and negative reputation of this label to rest for both ourselves, and our patients.