Are you in the same room as them

I had an interesting conversation with my Wife recently. This was following an appointment she had to get a new contact lens prescription. She said that she’d love to see the world through my eyes and was curious to see what might be different. I initially joked about her finally being able to see the top shelves at shops (she’s not very tall), and we spoke about how everyone’s personal experiences change the way they perceive what they are seeing and experiencing.

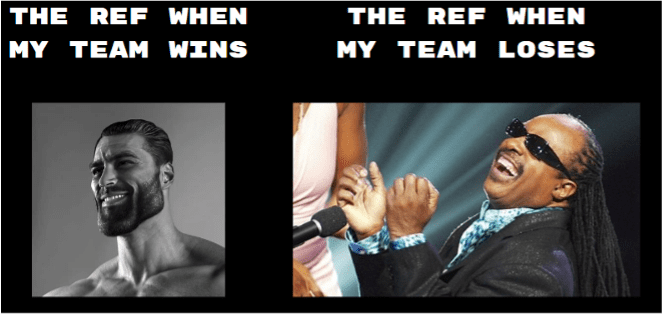

Another way of considering these differences in perspectives could be through a sporting example.

When one of your teammates attempts to take the ball, but misses and crashes into an opponent, you’re probably quite likely to see it as a simple mistake, or even a reasonable outcome, because you know them personally and know that it wouldn’t have been intentional. The other team though, will probably have some not-so-kind words with your teammate after some push and shove. And no matter what, one team will usually think the ref has made one of the worst calls ever seen, and it’s almost like the two teams aren’t seeing or playing the same game.

We must consider how our views differ from our patients in clinical practice as well – it’s important for us to do our best to understand our patient’s experiences, and what perspective that creates for them, before we can hope to share our own views, otherwise, like the sport analogy above, it could feel like we’re not in the same room as them.

This is crucial to a person-centred approach, which I’m sure we’re all doing our best to incorporate. However, it is easy to get caught up in the rush of our clinical practice, and maybe we don’t quite meet this as effectively as we could.

A patient’s pain and injury experience are greatly attributable to what experiences and expectations they have on their condition, and this will dictate what actions they take in their pain and injury management, as well as how they will engage with any advice or treatment that you provide. So, before you can do some movement-based treatment with a patient experiencing back pain who may be fearful about moving, you’ll need to understand why they personally feel they need to do that, and address that in the beginning.

A very effective way to do this is to phrase your questions openly, beginning them with prefaces like; “Can you tell me what you think may happen if…”, or “What are you most afraid of happening if you were too…”.

We don’t want to stop after these questions either, follow up again and ask your patient to explain what it is that makes them feel that way, and how that impacts them personally. Challenge for a deeper level of understanding until you can both feel confident that you are seeing things from the same perspective.

You may have heard the story of Sakichi Toyoda, the founder of Toyota, and the five why’s – he found that he could usually get to the root cause of an issue in his business by asking why, five times over, and this was how to truly understand and solve problems in the business. The number of why’s isn’t what we need to focus on, but the idea that we can reveal another layer of understanding as we continue to ask further questions each time, instead of stopping superficially.

It’s easy to fall in the habit of asking your first question and simply following this immediately by empathising with the patient and repeating what they’ve said in your own words. I’ve found this extremely beneficial in my own practice, but there have been occasions where the individual I was speaking with would say, “That isn’t quite what I was getting at, I don’t think you understand exactly what I’m saying.”

So, to help avoid this, after you’ve asked your questions to better understand your patient and their experiences, prefacing your understanding of their situation with something like, ‘So if I’m understanding correctly, you’re… explain xyz concerns… Would you say that matches what you’re experiencing well?’I think it’s important for us to be patient when paraphrasing concerns, and more generally, through communicating with our patients. Asking more questions and probing deeper into their perspectives, will be useful in helping you be able to better understand their fears, behaviours, and beliefs, and their engagement with your treatment and advice.