The Power of the Inverse

Unlike many of my peers, I had enjoyed mathematics through high school, particularly algebra and inverse functions. I’ve not continued with any mathematical study since then, but I do consider the usefulness of these exercises in the way of conversation and reasoning almost daily.

Consider the common expression; “Something is better than nothing”. I’ve struggled to truly accept this for almost as long as I can remember. Going for a 5- or 10-minute jog instead of 30-minutes just didn’t seem to have any point to it. I thought it wouldn’t be a sufficient stimulus for change in any sense.

This reasoning found it’s way into practice for me, where I’d initially overprescribe exercise and activity for some patients. A common response was that there was no adherence to the advice.

What changed this bias for me was inversing the common expression –

“Nothing is better than something”

This clearly isn’t true (as long as a patient’s presentation requires complete bed rest!) and I was almost immediately more agreeable. I challenged myself a little further along the same lines –

“Nothing isn’t better than something”

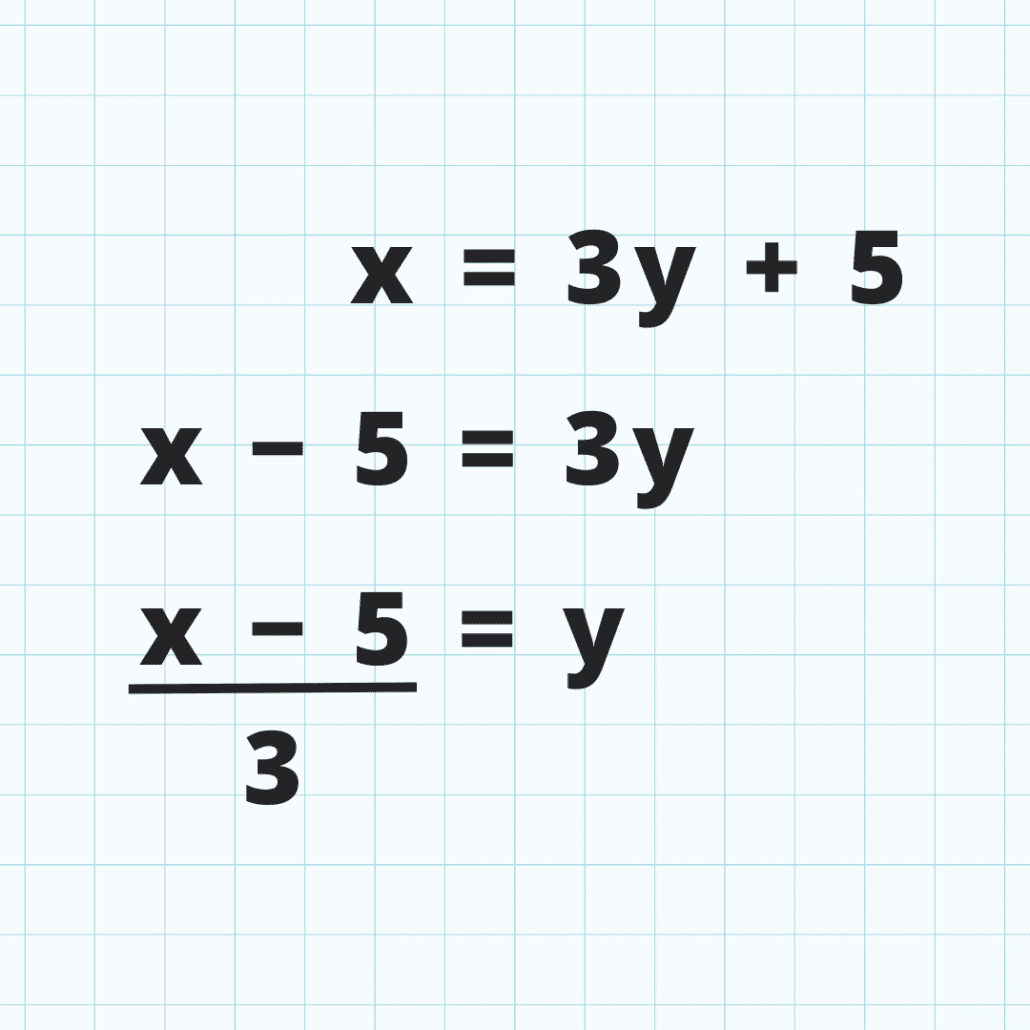

This is a better example of what inverse functions are in mathematics. Rearranging the letters and numbers in a formula, keeping it consistent as you apply arithmetic to change what the subject of the equation is (x and y) –

The phrases share the same meaning, but the framing and context conveyed can be interpreted very differently.

With the first statement, the ambivalence that I faced was that if there wasn’t a sufficient challenge. My focus was what was missing from an optimal situation, not what was gained from the action being taken.

The inverse expression made me challenge this mindset in a way that I hadn’t previously applied any rebuttals too – I simply agreed that not taking a short jog, was clearly less beneficial than some activity.

I could then explore what were the other reasons I didn’t run. I realised that one of the barriers to this action was thinking that the extra washing for a short run felt like it wasn’t worth it. This was an easier barrier for me to deal with than initially thinking it was the run that was not beneficial.

Consider this clinical example of using this framework –

You might initially ask your patient how they relieve their painful symptoms, to which they might say they have a few drinks each night and they feel more relaxed and less pain. If you don’t challenge this action with the inverse, it could remain quite easy to continue justifying the temporary relief, rather than making the lifestyle changes for longer-term change. This is an action that may have had months, or years of reasoning to justify it. Further education on the topic can just feel dismissive and offensive to the patient’s presentation and actions.

So, what does inverse reasoning look like for this?

Clinician (C): Reducing the amount of alcohol consumption would be beneficial for your pain.

Patient (P): It might be. But it helps me relax after a stressful day at work. I enjoy having a few drinks with dinner and then winding down after. I’d rather that than still being uncomfortable for the whole day.

C: Having a few drinks each night helps you relax more. That’s better than the sleep quality and further impacts to pain and function for you?

P: Well, maybe not entirely. But it’s better for that moment. I don’t have to think about the pain as much after dinner.

C: It helps you escape the pain each evening – that’s great you have some downtime. So, the temporary relief is better than longer-term change if you were making other lifestyle changes then?

P: It’s easier for me now. But I’d obviously like the pain to reduce throughout the whole day, not just in the evenings.

C: And continuing with the temporary relief is better than the longer-term change whilst it’s easier for you to do.

P: Well, it’s not better. The last time I got help for this I was given 20-minutes of exercises to do each day. I couldn’t always make the time for it, and I thought that meant it wasn’t going to help make any change if I wasn’t consistent every day.

With each comment that the clinician made, more information was provided by the patient to reveal the barriers, motivations and sense of control the patient felt.

The patient explores their situation deeper than initial reasoning and justification for actions as a result of the therapist’s lead. This is something that can easily adapt to questioning other lifestyle choices, adherence to exercise programming, or psychosocial aspects.

Fostering conversations that help explore contradictory ideas in a supportive manner helps cultivate change, leading to greater motivation, adherence, and receiving of education.

Importantly, written conversations like the above can sound dry and direct. Implementing this into actual examples needs to be supported with empathic verbal and non-verbal communication for more effective outcomes. Both understanding and respecting the patient’s perspective and reasoning for their actions is necessary, less they may feel their opinions are invalidated.